Fathers and Sons

- Hilary Sterne

- Jan 25, 2024

- 6 min read

Updated: Feb 1, 2024

By Hilary Sterne

This is from the wayback machine. A story about the death of a parent that was commissioned but never published by a now-defunct magazine. (I've worked for a bunch, including InStyle, Parade, Oprah, Readers Digest, GQ, Elle, etc.)

We came as messengers that Christmas, my husband and I, hoping to offer something other than gift cards and egg nog and peppermint bark. Did we joke about choirs of angels and wise men who traverse afar? I don’t remember. I just remember announcing “I’m pregnant,” as we walked through the door of my parents’ apartment in the assisted living facility where they made their home. I was somehow, against crazy stupid odds, expecting my first child at the age of 40 and I’d arrived to tell them in person, even though I hadn’t gotten the all-clear from the genetic counselor, a call that would come a few days later on my 41st birthday.

My mother stared at me for a moment and then said simply, “Oh,” before turning and walking out of the room. I followed her into the tiny kitchen, where she was bent rifling through the refrigerator. “What’s the matter? I asked. “I thought you’d be happy for me but you seem upset. Is something wrong?” “I have some news, too,” she said. “Your father has Alzheimer’s.” And that was how it all began. Two linked journeys. One into darkness and one into light.

My Dad and Me

I had always admired my father for many things, things I hoped I shared. He was witty, brilliant, outwardly cheerful (though inwardly brooding). But our relationship was one of brute defiance and clashing wills. He was a composer and musician, a professor who taught graduate composition seminars but also huge, popular lecture classes. When we were out together, we would sometimes be greeted by a former student: “I will always remember your class…you are my favorite teacher ever…thank you for making me appreciate something I’d never have otherwise listened to.”

Everyone loved my dad. Except me. Not always. After raging at each other for years, we arrived, blinking and battered, to a place of stunned acceptance, and once I left home I would send him books we would then discuss together. “Read ‘A Small, Good Thing,” I’d say. “That’s the best one.” “Beautiful,” he’d later tell me. “The best one. ”

My dad’s handwriting was tidy and distinctive, his music neat dots and strokes composed with a fountain pen and blue-black bottles of Schaeffer Scrip ink, but he was often lost in his own thoughts. Still, when he called my mother, panicked, from the side of a road he drove nearly every day and said he didn’t know where he was, she knew something was terribly wrong.

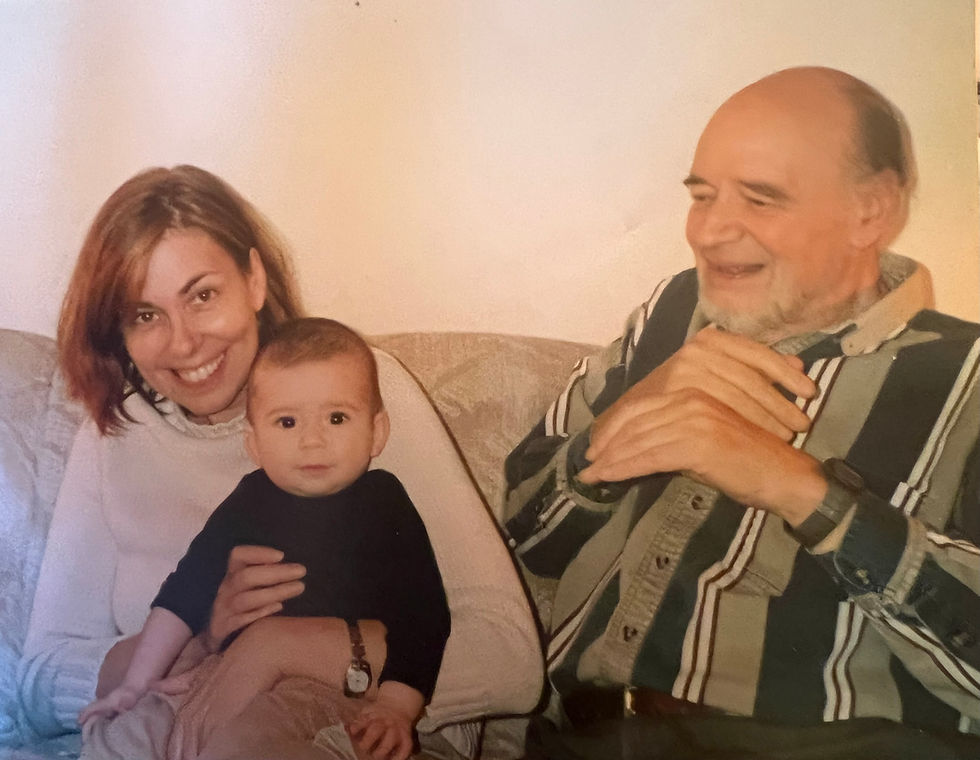

Our son T was born a few months later, and my dad seemed mostly fine despite the diagnosis. We visited soon after, bundling T in a leather baby Bjorn and staying at a nearby hotel. In our family, it’s traditional to give musical stuffed animals as baby gifts, and my mother presented us with one that played Brahm’s lullaby. Its neck was long, its fur solid cream, and two fuzzy nubs protruded from its head. A baby albino giraffe? “Dad, what is it?” I asked. My father laughed. “He’s a mythical beast!”

I would remember those words long after he wasn’t fine, after he forgot the words “mythical” and “beast,” after he forgot who he was, after he could no longer forget, since forgetting implies the ability to remember and he could do nothing but stare. First came a string of incidents, bewildering and frightening, that none of us could predict. He tried to urinate in a bush as he walked to a neighbor’s; he used the hand towels in the bathroom as toilet paper. One night he was taken by ambulance to a psych ward after he tried to attack my mother, a man who was once a renowned scholar of Renaissance music now as wild and senseless as a rabid dog.

I visited him one spring after that and we sat outside in the garden. Clots of blossoms waved in the fruit trees and bruised tulip tree petals lay strewn on the brick footpath. “Train,” my father said. “Hear the train? WOOO!” But there was no sound beyond birdsong in that little garden high on a hill, a garden that could only be entered by punching a code into a keypad. Soon there would be no train inside his head, either, and no garden, as it was razed to make room for more people like him, people who sat in a locked place and listened for the whistles of faraway trains.

My Dad and T

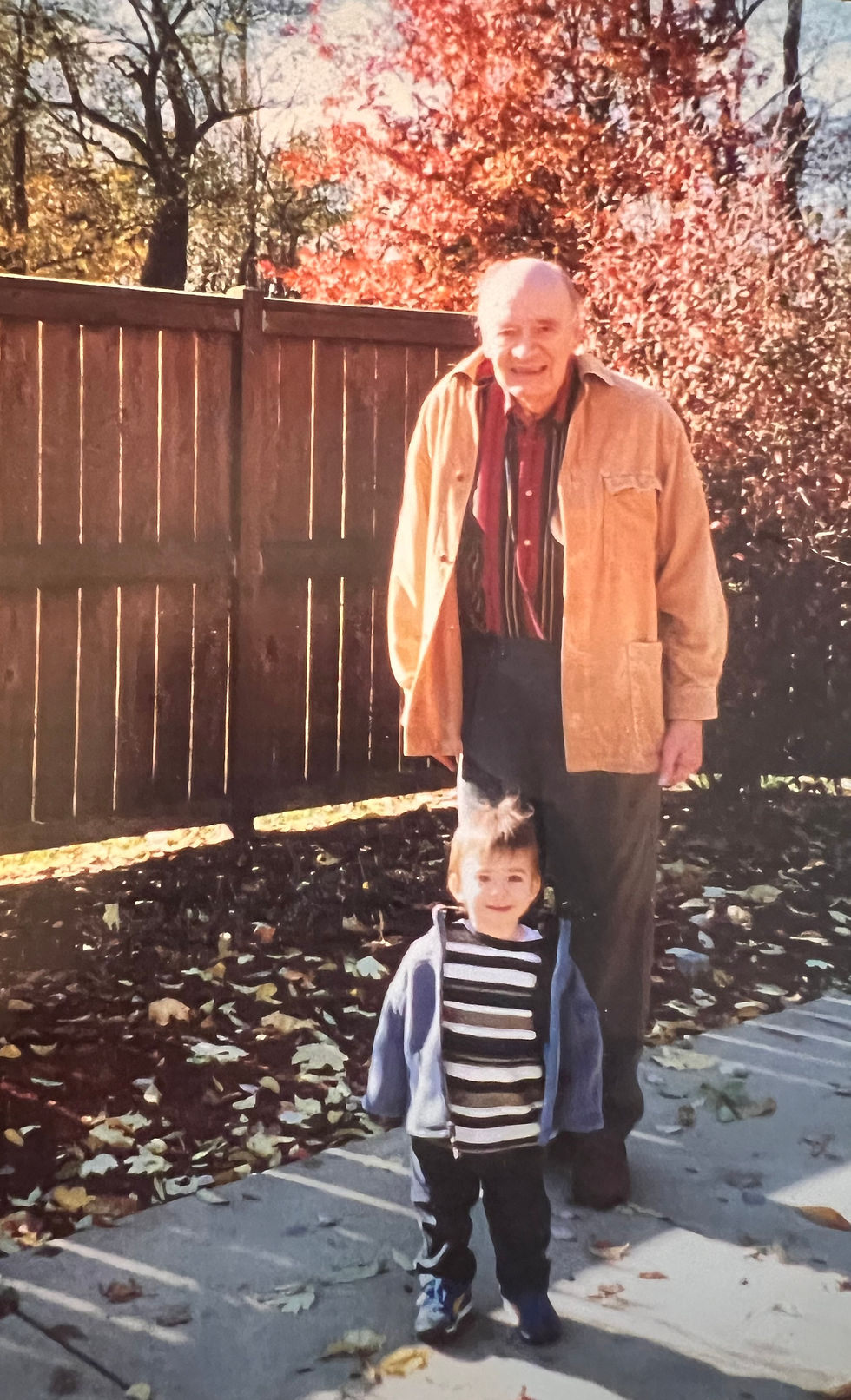

When he grew to be a toddler, T could bring my dad back from the edge of madness. Neither of them spoke all that intelligibly, but no matter. Born more than 80 years apart, they were the same neurological age, and they communicated in their own way. They would pull out boxes of wooden blocks in the playroom of the nursing home where Dad now lived, build them up and and knock them down, T chortling while Dad smiled and stroked a baby doll in his lap.

My mother made a saucer-sized button from a photograph of T wearing a Superman cape that streamed behind him as he ran headlong on his tiny legs, and it became my father’s talisman. He insisted it be pinned to his shirt every day. “Your dad sure loves that boy of yours,” the nurses would all say. And then one day even T couldn’t wriggle through the maze of plaques and tangles in Dad’s brain anymore.

The Last Day

The summer he died, I had just been fired from a job I’d taken three days before my husband was diagnosed with Stage 4 cancer. I flew home feeling freed but also feeling a knot of foreboding, somehow sensing this might be the end of everything. The next morning, while the light was still silvered, the nurse called to wake us. My mother and I went to my dad’s room, chilled and smelling of disinfectant, and sat on either side, talking to him and stroking his arms, listening to his breath.

At one point I said, “Mom why don’t we play his music for him ?” I went to the empty Zumba room down the hall to find a boom box and to my mom’s apartment to find a CD and returned in time to fill the room with his music. His breathing slowed and slowed until finally the only sound was that of my father as he once was and would always be, while I waited for the next breath that never came. My mother wept and called him by the nickname only she ever used.

My dad had been dying for years, and my sisters and I assumed my mom had planned his funeral long before, one that included music and poetry and the sorts of funny anecdotes my dad was known for telling, but we were wrong. “I can’t do it. Please don’t make me do it,” she begged We told her we knew it was hard but that she would most likely regret not letting people say goodbye. In the end, as a concession, we made a small announcement and held the funeral service in the church where I’d grown up.

The man who’d been admired by so many was mourned by nearly no one. His children, a handful of friends, a little boy who no longer wore a red cape but instead a borrowed black suit. There were sandwiches and urns of coffee in the church reception hall, and my nephew was presented with an American flag folded like a turnover, a gift from the Army for my dad’s service in the military band, which saw off the wartime troops at the Port of Los Angeles with Bob Hope and Benny Goodman.

What Endures

My son doesn’t look much like my father, though it seems he has inherited some of his musical talent. He has my dad’s brown eyes, but he mostly looks like me. Except in one photo of T at his baseball camp, a photo the camp chose to use in a promotional flyer this year. T is smiling, wearing a too-big batting helmet, running towards the camera as in his superhero days, arms spread wide, thumbs pointing up.

There are stacks of the flyers at the camp facility, where I volunteer and where T takes lessons, and I always smile when I see one. “Mom, why do you like that picture so much?” T asks. “I guess because you look so happy in it,” I say. “And because you look a little like Grandpa Colin, the way you’re smiling.” “I do?” asks T, any real memory of my dad having vanished as surely as my dad’s memories of him once did. “You do,“ I say.

When my dad comes to me in my dreams, he is neither as he was before he got sick nor as he was after. He appears as those we love appear to us in dreams: something entirely different but altogether familiar. He is hovering over T, strong and powerful, magnificent scaled wings spread in protection, eyes watchful, heart beating. He is high above and yet so close his breath is on him. He’s a mythical beast.

Ohhhh Hilary, how beautiful and heartbreaking and perfect.